Not hard to see why I like this one!

“We have only to follow the thread of the hero-path. And where we had thought to find an abomination, we shall find a god; where we had thought to slay another, we shall slay ourselves; where we had thought to travel outward, we shall come to the center of our own existence; and where we had thought to be alone, we shall be with all the world.”

– Joseph Campbell, The Hero With a Thousand Faces

- – - – - – - – - – - -

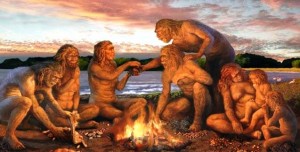

We begin with a day in the life of early humans.

Life is hard. Lifespans are short. An early death is the norm, either from disease or from danger. At night, tribes huddle around fires for warmth, food, safety, and security. But they also gather around community fires for something else that is nearly as important.

They come to hear stories.

The elders of the tribe know that because life is nasty, brutish, and short (to borrow a phrase from Thomas Hobbes), the members of the tribe are afraid. Those members – many of them sick, hungry, injured, or tired — seek some understanding of their misery, some sense of meaning to buoy their spirits.

As the elders begin reciting their stories, the huddled masses seated around the fires, in desperate need of comforting, lean forward in eager anticipation.  They may not be consciously aware of what they need from these stories, but their need is strong nevertheless.

They may not be consciously aware of what they need from these stories, but their need is strong nevertheless.

They may not be consciously aware of what they need from these stories, but their need is strong nevertheless.

They may not be consciously aware of what they need from these stories, but their need is strong nevertheless.

The stories told by the elders are hero stories. They tell of ordinary men who are called to go on great journeys or who face formidable life challenges. The protagonists in these stories are described as small, weak underdogs who must transform themselves in important ways to overcome long odds to succeed. These heroes receive assistance from enchanted and unlikely sources. Remarkable cunning and courage are required for these men to triumph. Once successful, these heroes return to their original tribe to bestow a boon to the entire community.

As tribe members soak in these inspiring hero stories, they themselves are affected in profoundly positive ways. Thanks to these stories, fears are allayed. Hopes are nourished. Important values of strength and resilience have been underscored. Life now has greater purpose and meaning.

- – - – - – - – -

Today’s humans are no different from early humans in their thirst for heroes and heroic leadership. The attraction to greatness in other human beings is as strong as ever. Our goal here is to outline a set of psychological events responsible for the powerful and inescapable allure of strong heroic figures.

We propose that a complex web of phenomena exist that capture the human drive to create heroes in our minds and hearts, in storytelling, in our behavior, and in virtually every crevice of every human culture. We call this web of phenomena the Heroic Leadership Dynamic.

We use the term dynamic, and its multiple meanings, intentionally. In its noun form,dynamic refers to an interactive system or process. Used as an adjective, dynamicdescribes  this system or process as energizing and always in motion, a system that drives people toward heroes and toward hero storytelling.

this system or process as energizing and always in motion, a system that drives people toward heroes and toward hero storytelling.

this system or process as energizing and always in motion, a system that drives people toward heroes and toward hero storytelling.

this system or process as energizing and always in motion, a system that drives people toward heroes and toward hero storytelling.

We argue that the human desire to generate heroes implicates a complex system of psychological forces all geared toward developing heroes, retaining them as long as they prove psychologically useful and, yes, even discarding heroes when they’ve outlived their usefulness.

The Heroic Leadership Dynamic can almost be described as a story in itself, with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

At the beginning sits our craving for heroes, borne out of a longing for an understanding of the vicissitudes of life. Our early ancestors gathered around fires at night for reasons that went far beyond the physical benefits produced by fire. We propose that for these early humans, the drive to create heroism in their minds, in their stories, and in their culture was as necessary for their mental and emotional well-being as the fire was for their physical well-being.

And we suggest that humans today are no different at all.

Our human craving for heroes, our need for the psychological benefits that heroes offer, and our desires over time either to retain our heroes or to repudiate them, all comprise the constellation of phenomena that are implicated in the Heroic Leadership Dynamic.

And yes, an important part of the dynamic — maybe the most important — is that it offers a framework for understanding the drive that all of us have to become heroes ourselves, given the right circumstances.

In Part 2 of this series, we dive into the details of the psychological forces underlying the Heroic Leadership Dynamic. Here is Part 2.

This series is based on a chapter that will appear in our forthcoming book,Core Concepts in the Psychology of Leadership, published by Palgrave Macmillan.