by Maria Popova

What language and symbolism have to do with mood and how light exposure and sleep shape our mental health.

“Depression is a disorder of the ‘I,’ failing in your own eyes relative to your goals,” legendary psychologist Martin Seligman observed in hisessential treatise on learned optimism. But such a definition of depression, while true, appears somehow insufficient, overlooking the multitude of excruciating physical and psychological realities of the disease beyond the sense of personal failure. Perhaps William Styron came closer in his haunting memoir of depression, Darkness Visible, where he wrote of “depression’s dark wood,” “its inexplicable agony,” and the grueling struggle of those afflicted by it who spend their lives trying to trudge “upward and outward out of hell’s black depths.” And yet for all their insight into its manifestations, both the poets and the psychologists have tussled rather futilely to understand depression’s complex causes and, perhaps most importantly in terms both scientific and humanistic, its cures.

That’s precisely what psychologist

Jonathan Rottenberg sets out to do in

The Depths: The Evolutionary Origins of the Depression Epidemic (

public library) — an ambitious, rigorously researched, and illuminating journey into the abyss of the soul and back out, emerging with insights both practical and conceptual, personal and universal, that shed light on one of the least understood, most pervasive, and most crippling pandemics humanity has ever grappled with. (A sobering note to the hyperbole-wary: At any given point, 22% of the population exhibit at least one symptom of depression and the World Health Organization projects that by 2030, depression will have led to more worldwide disability and lives lost than any other affliction, including cancer, stroke, heart disease, accidents, and even war.)

Rottenberg takes a radical approach to depression based not a disease model of the mind but on the evolutionary science of mood — a proposition that flies in the face of our cultural assumptions that have rendered the very subject of depression a taboo. He puts this bind in perspective:

Because depression is so unpleasant and so impairing, it may be difficult to imagine that there might be another way of thinking about it; something this bad must be a disease. Yet the defect model causes problems of its own. Some sufferers avoid getting help because they are leery of being branded as defective. Others get help and come to believe what they are repeatedly told in our system of mental health: that they are deficient.

[…]

People still feel inclined to whisper when they talk about depression. Depression has no “Race for the Cure”; this condition rarely spawns dance marathons, car washes, or golf tournaments. Consequently, the lacerating pain of depression remains uncomfortably private.

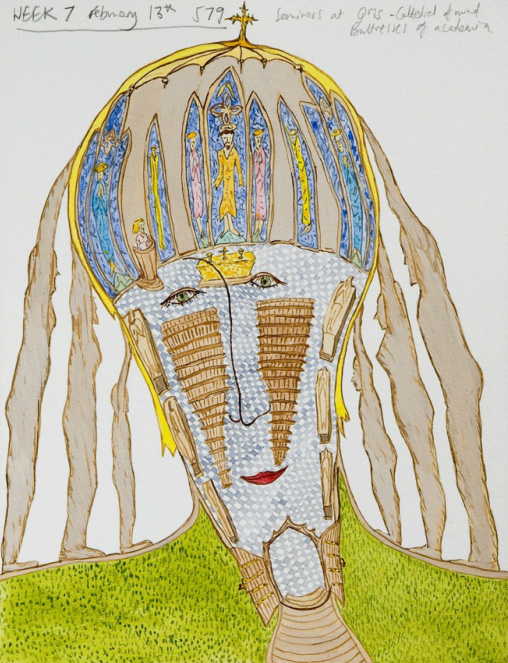

Illustration by artist Bobby Baker from 'Diary Drawings: Mental Illness and Me.' Click image for details.

Rather than subscribing to this broken deficiency model of depression, Rottenberg argues that affective science — the empirical study of mood — lies at the heart of understanding the condition. Defining moods as “internal signals that motivate behavior and move it in the right direction,” he argues that our bodies are “a collection of adaptations, evolutionary legacies that have helped us survive and reproduce in the face of uncertainty and risk” and paints the backdrop of understanding depression:

The mood system … is the great integrator. It takes in information about the external and internal worlds and summarizes what is favorable or unfavorable in terms of accomplishing key goals related to survival and reproduction.

[…]

Once a goal is embarked upon, the mood system monitors progress toward its attainment. It will redouble effort when minor obstacles arise. If progress stops entirely because of an insuperable obstacle, the mood system puts the brakes on effort.

Under this model, mood has an evolutionary function as a mediator of survival strategies. Rottenberg cites a number of experiments, which have indicated that negative mood incites one’s psychoemotional arsenal when a task becomes too challenging. For instance, when study participants are deliberately put in a negative mood and asked to perform a difficult task, their blood pressure spikes — a sign that the body is being mobilized for extra alertness and effort. But if the task is made insurmountably difficult, so much so that success stops being possible, the spike no longer occurs and the mood system dials down the effort. In that sense, mood — the seedbed of depression — isn’t an arbitrary state that washes over us in a whim, but a sieve that separates the goals worth pursuing from those guaranteed to end in disappointment.

Rottenberg argues that our relationship to the mood system is shaped by the way we talk about it and is mired in toxic cultural constructs that bleed into our language:

One of the amazing things about the mood system is how much of it operates outside of conscious awareness. Moods, like most adaptations, developed in species that had neither language nor culture. Yet words are the first things that come to mind when most people think about moods. We are “mad,” we are “sad,” we are “glad.” So infatuated are we with language that both laypeople and scientists find it tempting to equate the language we use to describe mood with mood itself.

This is a big mistake. We need to shed this languagecentric view of mood, even if it threatens our pride to accept that we share a fundamental element of our mental toolkit with rabbits and roadrunners. Holding to a myth of human uniqueness puts us in an untenable position. For one thing, it would mean that we deny mood to those humans who have not yet acquired mood language (babies) or have lost mood language (Alzheimer’s patients). Toddlers, goats, and chimps all lack the words to describe the internal signals that track their efforts to find a mate, food, or a new ally; their moods can shape behavior without being named. Language is not required for moods. All that is needed is some capability for wakeful alertness and conscious perception, including the perception of pain and pleasure, which is certainly present in all mammals.

Still, Rottenberg cautions, “what we say about our feelings is only one window on mood” — we need, instead, to examine a variety of evidence in the mind, brain, and behavior to paint a dimensional picture of mood and depression. In fact, part of the puzzle lies in the crucial difference between feelings, or emotions, and moods — emotions are more instantaneous and short-lived responses compared to moods, which take longer to germinate and longer to wither out. Moods, Rottenberg explains, “are an overall summary of the various cues around us [and usually] are harder to sort out.” Our deeper reliance on moods rather than feelings is one of the things that make us human and different from other species, a difference empowered by our use of language and symbolism:

Our heavy reliance on symbolic representation also makes the precipitants of low mood more idiosyncratic in our species than in others. We become sad because Bambi’s mother dies, because there are starving people a continent away, because of a factory closing, because of a World Series defeat in extra innings. Though there is a core theme of loss that cuts across species, humans’ capacity for language enables a larger number of objects to enter, and alter, the mood system.

Illustration by artist Bobby Baker from 'Diary Drawings: Mental Illness and Me.' Click image for details.

And yet for all our emotional sophistication, we remain strikingly blind to many of the real triggers and causes of moods, instead falling back on our

penchant for psychological storytelling. Rottenberg ties this back to depression:

Despite our deep yearning to explicate moods, the average person cannot see many of the most important influences on mood. As the great integrator, the mood system is acted on by many potential objects, and many of the forces that act on mood are hidden from conscious awareness (such as stress hormones or the state of our immune system). Left to our own devices, the stories we tell ourselves about our moods often end up being just that. Stories.

[…]

We must understand the ultimate sources of depression if we are ever to get it under control. To do so, we need to step back and replace the defunct defect model with a completely different approach. The mood science approach will be both historical and integrative: historical because we cannot understand why depressed mood is so prevalent until we understand why we have the capacity for low mood in the first place, and integrative because a host of different forces (many hidden) simultaneously act on people to impel them into the kinds of low moods that breed serious depression.

But before we are tempted to file away low moods as an affliction to be treated, Rottenberg offers a necessary neutrality disclaimer, pointing out that both high and low moods have their advantages and disadvantages:

We are born with the capacity for both high and low moods because each has, on average, presented more fitness benefits than costs. Just as being warm blooded can be a liability, high moods are increasingly understood as having a “dark side,” sometimes enabling rash, impulsive, and even destructive behavior. Likewise the capacity for low mood is accompanied by a bundle of benefits and costs. Seen this way, depression follows our adaptation for low mood like a shadow — it’s an inevitable outcome of a natural process, neither wholly good nor entirely bad.

So what might be the evolutionary advantages of low moods? Several theories exists. One proposes that low moods help dampen agitation in confrontation, thus de-escalating conflicts — when a loser yields rather than fighting to the death, he or she is able to survive rather than perish. Another paints low mood as a “stop mechanism” that, just like the task studies suggested, prevent the person from exerting effort towards a goal that is either unattainable or dangerous. A different theory conceptualizes low mood as a tool for making better decisions, putting us in more contemplative mindsets better suited for analyzing our environment and solving particularly hard problems.

In fact, the latter is something repeatedly confirmed by experiments, most notably in the pioneering work of psychologists Lyn Abramson and Lauren Alloy, who termed this role of low mood depressive realism. Their work has inspired multiple other experiments, including this 2007 study:

Australian psychologist Joseph Forgas found that a brief mood induction changed how well people were able to argue. Compared to subjects in a positive mood, subjects who were put in a negative mood (by watching a ten-minute film about death from cancer) produced more effective persuasive messages on a standardized topic such as raising student fees or aboriginal land rights. Follow-up analyses found that the key reason the sadder people were more persuasive was that their arguments were richer in concrete detail [suggesting that] sad mood, at least of the garden variety, makes people more deliberate, skeptical, and careful in how they process information from their environment.

These positive uses of negative moods may seem at first counterintuitive, but Rottenberg reminds us that “multiple utilities are the hallmark of an adaptation.” He puts things in perspective:

One way to appreciate why these states have enduring value is to ponder what would happen if we had no capacity for them. Just as animals with no capacity for anxiety were gobbled up by predators long ago, without the capacity for sadness, we and other animals would probably commit rash acts and repeat costly mistakes.

In support of this conception, Rottenberg cites a wonderfully poetic passage by Lee Stringer from his essay “Fading to Gray,” found in the altogether fantastic 2001 volume

Unholy Ghost: Writers on Depression:

Perhaps what we call depression isn’t really a disorder at all but, like physical pain, an alarm of sorts, alerting us that something is undoubtedly wrong; that perhaps it is time to stop, take a time-out, take as long as it takes, and attend to the unaddressed business of filling our souls.

(What gorgeous language, “the unaddressed business of filling our souls” — rather than an affliction, isn’t that the ever-flowing lifeblood of human existence?)

Cover illustration for P.M. Hubbard's 'Picture of Millie' by Edward Gorey. Click image for details.

Still, Rottenberg is careful to point out that severe depression, far from being evolutionarily beneficial, is absolutely crippling, marked by “distorted thinking that appears to be the polar opposite of depressive realism.” In fact, what is perhaps most perplexing about the condition is that scientists don’t yet have a litmus test for when low mood tips over from beneficial to perilous, no point on the mood spectrum that clearly delineates the normal from the diseased. Rottenberg proposes that mood science is the key to honoring the nuance of that spectrum. He differentiates between milder periods of low mood, which he terms shallow depression, and periods wherein the low mood is both long-lasting and severe, which he calls deep depression, and writes:

Shallow depression is adaptive, whereas deep depression is a maladaptive disease.

The strongest evidence for this spectrum model, rather than a binary division between wellness and disease, comes from the fact that shallow and deep depression share a set of risk factors, suggesting that mood, which varies along a continuum of intensity, is the common denominator. Rottenberg puts it elegantly:

Ignoring this would be like a weather forecaster using separate models to predict warm days and very hot days rather than considering general factors that predict temperature.

So what, exactly, seeds low mood? Rottenberg points to three distinct but interconnected triggers: explainability, evolutionary significance, and timing. He writes:

Modern psychological theories postulate that we recover more quickly from a bad event if we can readily explain it. We would expect, then, that events that generate mixed feelings and/or confusing thoughts would be a powerful impetus toward persistent low mood.

[…]

Events that present irresolvable dilemmas on themes that have evolutionary significance — like mate choice — are fertile seeds for low mood.

When the bad things happen also matters. Extensive research demonstrates that early life traumas, such as physical or sexual abuse, lay the groundwork for a slow creep of depression and anxiety.

He cites the example of a middle-aged woman suffering from lifelong “low-grade depression” and anxiety, who grew up with an alcoholic father in a household that vetoed any discussion of feelings. When a neighbor molested her at the age of thirteen, she kept the trauma to herself, believing that her mother would blame her and her father would explode in a rage. Rottenberg explains how these early experiences provide the psychoemotional backdrop for our adult lives:

Jan’s chronic feelings of anxiety and sadness are natural, the product of an intact mood system. In a world in which a child’s primary attachment figures — parents — are emotionally unavailable and unable to help when a trusted neighbor turns into an attacker, the mood system is ever forward looking. It assumes that, if the worst has already happened, it can and will happen again. Best to be prepared. Anxious moods scanning for danger (especially in relationships) and sad moods analyzing what was lost and why serve as the last lines of defense against further ruin.

Illustration by Edward Gorey from 'Donald and the…' Click image for details.

Triggers notwithstanding, Rottenberg points out that individual temperament is an essential component in people’s mood responses to the same events. He cites a study conducted after the 9/11 attacks which found that a month later Lower Manhattan residents who had been there on September 11 experienced wildly different degrees of depressive symptoms, ranging from crippling major depression to hardly any symptoms compared to their respective state on September 10.

This variation, once more, can be traced back to early childhood. Rottenberg cites the work of psychologist Jerome Kagan who has spent decades studying infants and found that temperament can be detected as early as in nine-month-olds, who exhibit “reasonably consistent and strong fear reactions to a variety of potentially threatening situations.” These early differences in temperament, Rottenberg argues, are likely to be heavily influenced by genes.

And yet, just like the mood spectrum, temperament isn’t a black-and-white game but an evolutionarily wise strategy:

Experiments by evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson also demonstrate that there is no “single best temperament.” In one condition, Wilson dropped metal traps into a pond containing pumpkinseed sunfish. A subset of the fish showed boldness and interest in investigating a novel object. This was a really bad move, as they were immediately caught, and had Dr. Wilson been a real predator, it would have meant the end of their genes. Another group of fish were wary and stayed back from the traps; they were not caught. This situation favored the wary fish.

In a subsequent condition, all the fish were scooped up, brought into a new environment, and then carefully observed. Here the previously wary fish had great difficulty adapting to novelty. They were slower than their bold compatriots to begin feeding, taking five more days to start eating. In this situation the survival of the bold fish was favored.

Noting that the single most indicative depression-prone personality trait is neuroticism, Rottenberg adds:

Like depression itself, temperaments that seed depression are neither wholly good nor wholly bad.

Pointing to two distinct sets of influences on mood — forces that make us vulnerable to long periods of shallow depression and ones that deepen existing shallow depression — Rottenberg makes a poignant observation about our culture’s growing

fetishism of happiness:

Our expectations about happiness have changed dramatically, and as they rise, ironically, are making low moods harder to bear than ever before.

Illustration by Edward Gorey from 'The Green Beads.' Click image for details.

Mood is about the mundane. Day-to-day routines — how we spend our time, how we care for our bodies and minds — continually shape our moods and can have a strong influence on whether low mood persists. Routines that build up physical and mental resources can raise mood. Other routines, woven into the fabric of modern life, are grossly misaligned with evolutionary imperatives and have the potential to seed low mood. Many of our most familiar routines seem almost perversely designed to wreak havoc on the mood system.

One mundane influence on mood is daily light exposure. After all, mood evolved in the context of a rotating earth, with its recurrent twenty-four-hour cycle of light and dark phases. Our species is diurnal, and the best chance of finding sustenance and other rewards was in the light phase (think about the challenge of identifying edible berries or stalking a mammoth). Consequently, we are configured to be more alert during the day than at night. Consistent with the link between light and mood, some clinically serious low mood is triggered by the seasonal change of shorter daylight hours. The onset of seasonal affective disorder, a subtype of mood disorder, is usually in winter.

Our newfound reliance on indoor light has effectively turned most people into cave dwellers. Artificial light is much fainter and provides fewer mood benefits than sunlight. When small devices that measure light exposure and duration were attached to adults in San Diego, one of the sunniest cities in the United States, it was discovered that the average person received only fifty-eight minutes of sunlight a day. What’s more, those San Diegans who received less light exposure during their daily routines reported more symptoms of depression.

(My reliance on this

light-therapy device, which has gotten me through many dreary New York winters, suddenly seems less trivial and less of a placebo effect.)

Illustration by Alessandro Sanna from 'The River.' Click image for details.

As a

champion of sleep, I especially appreciate the sobering evidence Rottenberg cites from a number of sleep studies:

Mood is lower after even one night of sleep deprivation. Moreover, brief experimental sleep restriction induces bodily changes that mimic some aspects of depression. It’s important to ponder the consequences of sleep deprivation now happening on a mass scale: more than 40 percent of Americans between the ages of thirteen and sixty-four say they rarely or never get a good night’s sleep on weeknights, and a third of young adults probably have long periods of at least partial sleep deprivation on an ongoing basis. Over the last century average nightly sleep duration has fallen. In 1910 Americans slept an average of approximately nine hours; that average had dropped to seven hours by 2002.

Part of the answer to the riddle of low mood, then, lies in contemporary routines that increasingly feature less light, less rest, and more activities that are out of kilter with the body’s natural rhythm.